We always had a family interest in bees and worms but in 1989 a friend shared a worm farming book and my interest geared up.

Instead of starting with the usual family sized commercially produced worm-bins I used Styrofoam boxes then quickly graduated to in ground double block walled beds in 1996-1997.

In Mudgeeraba we had 6 beds.

We fed animal manure, abattoir paunch, spent cardboard pulp, biosolids, hessian bags, paper, cardboard, ground up green wastes and hays. Feeding approximately 1 inch (0.0254m) twice a week. Each inch, once the particle size was reduced by combined microbe and worm-crop grinding, became approximately 0.5 inches of castings.

In mid-1997 ABC’s Landline produced a program featuring two revolutionary projects using worm recycling methods.

The one in Canberra had a few small compost-windrows outside and 6 small block worm beds inside. They were composting various organic wastes and then placing the tromelled fines onto the worm beds to become ‘castings’.

They bagged their end product and labelled it “Pure Worm Castings”. However, when I inspected the workings in the worm bed there were very few worms. Far too few to produce that much castings. I was disappointed.

Spurred on by the growing interest of the day we proceeded to build extra beds on a property in Tallai, Qld. This time we built 18 more beds

From 1997 to 1999 there was an exponential explosion of small worm projects in Australia.

Many new innovations appeared to assist the worm processes.

In the USA worm farming for bait worms was already a Billion Dollar business with approximately 150 registered businesses. Here in Australia we suddenly had in excess of 600 registered businesses and practically no-one making a Dollar.

Enter Vermitech – “the environmental solution” – Our competitor. In 1998 they contracted with Redland Shire Council who also sponsored them to set up steel framed worm beds near the local sewerage processing facility, close to the coast.

For some time Vermitech’s beds were exposed to the weather and thousands of Ibis birds. The weather can cause worms to leave their unnatural homes by the hundreds of thousands. Each Ibis can eat 1 kilogram of worms each time they feed – many times through each day. A large portion of the worm’s rations was very dried biosolids as part of the agreement with the Local Council. They were informed that they needed to have a very high carbon content in the mix in order for composting to be facilitated effectively. When asked why the large wood chips (not sawdust) were added, in front of hundreds of bused in officials, engineers, Council representatives, Government officials and other spectators from around the world, the glib answer given was, “to help the worms move through the slippery wastes”. We observed whole truckloads, from the local cannery, of single vegetable types, unprocessed and fed to their worms.

Worms kept leaving the beds in droves, due to weather and light exposure, unsuitable food and living environment, birds chowing down all through the day and unblended or processed wastes with wood chips imbedded.

The shade cloth rooves still allowed sunburn and the worms kept leaving.

The weld-mesh bottoms to their steel beds would not allow the clumped and rock-hard wastes to pass through, even if it had been converted to castings – which it was not.

Each bed was dismantled and refitted with angled bars under the base so that the solid dry mass inside could be ‘mined’ from between the bars to harvest. When stockpiled then the ‘castings’, which should have passed through millions of worm’s digestive tracks, were ground with a hammer mill to a suitable size for bagging and sale.

Not long after, Vermitech had unsuccessfully honoured its 3-year contract with Redland Shire and after an extra 2-year extension the contract was cancelled and given to an ‘Environmental’ Service.

Around this time there was much inuendo and rumour about ‘pyramid’ schemes and ponzi deals, investors who bought contracts to supply worms and or castings for a ‘collective’ marketing group who were unable to sell anything. So, things turned sour after just a few years and ‘worm farming’ became something of a painful memory to many.

Over these years we continued, as a family, to work and experiment with our worm beds, blending feeds, harvesting, collecting and transporting ‘colonies’ of starter worms, designing more functional beds and worm-specific equipment. Because so many projects had difficulty in maintaining their vital worm ‘herds’, we were able to supply worms and thereby gained access to a number of experiments. One sponsored by an ‘Environmental’ Firm in 1999 at Swanbank.

The operator told us he had 18 months experience with worms. He would roll up the sides of the shelter and dump piles of chunky biosolids on his windrow-of-sorts. His worm-workers would regularly go ‘on strike’ to fight for better conditions – a better variety of foods, suitably moist, cool environment, correct pH and less sunlight. When that failed, they would leave in bulk.

We were fortunate to basically perfect this art: in every 8 to 12 weeks (if bad weather), our worm population – all sizes – would increase sufficiently that we could ‘gently’ extract up to 40% from any sized bed and produce another functional bed. After a further 8 to 12 weeks, we were able to extract from both beds and start another two, and so on, all through the year.

Otherwise, if you breed too many worms and leave them there, the oldest and best breeders will escape to ‘pioneer’ new locations away from your beds and they leave your beds to the juvenile worms. When that happens, the babies do not breed till 3 months old and then minimally until they are mature at 1 year old. That can really slow things down in the organics recycling.

‘Vermitech lose worm contract’ article states: An ‘environmental’ company “was considered to offer the best option for Council as they provided both a good environmental solution as well as value for money”, Mayor Don Seccombe said.

Let’s look for a moment.

So, this is where raw sewerage biosolids were dumped after, what appears to be lime from recycled cement was mixed through with an excavator. The top crusted white and after a year the inside was just a putrid as before – not composted at all. Not as per the proposal to Council. This slop stayed there for up to a year and was harvested, sold for $10 per tonne to cane farmers in Mackay, Qld – ready to be flushed by storms into the reefs.

Meanwhile, we were invited by Queensland State Development Officers to attend a meeting with 7 delegates from “a city in China with 20 million citizens, in a province with over 200 million citizens” – Shanghai. Each was a university professor as well as, the Minister for Agriculture, The Minister for Finance … etc. They requested that we design a system to handle 50 million Tonnes of organic waste per year.

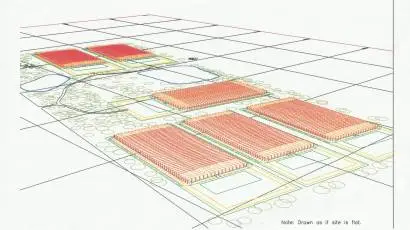

After careful consideration a design was struck. It had to be a project on the smallest parcel of land practical as land was considered to be at a premium. Normal above-ground worm bed formats would require at least 28,521 acres however we designed a system that was 10 levels high and fitted on just 352 acres.

The Chinese delegates were very please and took us aside to ask, “Could you give us the technology, designs etc for FREE and have your government pay you?” Our hosts at State Development were more than reluctant to agree.

Next the delegates asked for a design to handle just 1800 tonnes per year, for no charge. I suggested that they would probably build it at the University and then upscale it themselves once they could copy the technology. They agreed with my thinking, so again I had to decline. Strangely State Development Officers could not see the funny side of my refusal.

We were again approached to design and operate a large project based in Clifton Qld and financed from US funding. The plan was a project to handle 850,000 m3 of selected organic wastes per year, There was then sufficient need for such projects that we could have built 20 more to try to handle the available Organic Wastes on just the East Coast of Australia.

All the preliminary enquiries were undertaken, suitable land (66 hectares) with appropriate approvals from State, Department of Primary Industries, the Environmental Protection Agency and local Council was made available. Shade structures, beds, fire systems, cooling systems, sprinkler systems, roads in and out, vehicles, onsite equipment … etc., etc., where designed by various other global experts and made ready for action as soon as the funding landed.

We were introduced to the then Premiere of Qld and a number of his team. He said that he would finance half of the project with funds from the Heritage Fund which, at the time, he said, contained some 10 Billion Dollars. He would pay half. He would own half but control the entire project and then give it to the world. He saw clearly the potential environmentally and financially. Needless to say, we did not agree. The funding never did clear the International Banks.

We were contacted by a Malaysian Prince, the Deputy Prime Minister, and two mega wealthy Malaysian Businessmen. The Company, IndoWater who had the contracts for freshwater provision and sewerage treatment for Malaysia had, according to The W.H.O., provided the worst water pipes and services in the world for more than 10 years.

They had recently declared themselves bankrupt but not before being paid 12 years in advance. Apparently, you can do those things when relatives rule. The consequence was that 1600 sewerage treatment plants throughout all of Malaysia had stopped operating throughout all the country. On average, they said, more than 10,000 litres per hour from each facility was being pumped directly into rivers and the sea without treatment. They complained that they could not even swim in the sea without seeing direct evidence of the problem.

We were asked to design a system to handle the sewerage for all of Malaysia. Once underway we were advised that we would need to tender. No problem. Next the Government informed us that we would need to tender against IndoWater who were still the preferred contractors. At that point we all dropped out. IndoWater did not obtain all the contracts at that time – just most of them. It is hard to beat a ‘good’ system.

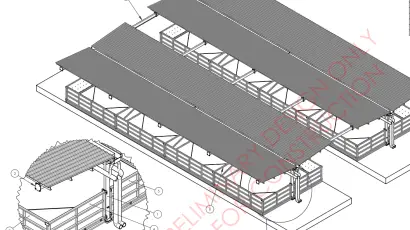

During 2018 we contracted an engineering firm to draw designs for modular, steel frame worm beds for large commercial projects.

They came up with beautiful drawings, using steel tube, 75mm x 50mm x double thickness and more, of beds that were so robust that we could literally fence in rhinos successfully. When we questioned the size and thickness of steel proposed, we were advised of the possible incredible internal pressure produced by moist soil material that would buckle the sides.

We advised them of the many types of ‘beds’ around the world that consisted of poly-fabrics and broom sticks, over a metre high that successfully handled organics to castings over many years, without ‘blowing out”.

That same year we design and fabricated a small wooden worm breeding bed, with the intent to grow sufficient worms to ‘power’ a larger bed which would power a larger bed and … you get the picture. Next we built a larger worm bed out of ply wood and scrap timber to see how much pressure would effect it’s sides. We used the extracted castings and worms, wet lucerne hay and fresh feed on top to start this new bed. Worked like a charm.

You may have noticed that the framework was deliberately inside and the ply on the outside with only a few screws holding the panels in place. If ANY internal pressure developed as the bed approached 1.1 metre deep it would easily push the plywood off the sides. Remenber, our castings – worm environment is maintained at 76% moisture content which should boulge out the sides of the bed but that the castings are a gradual half inch per feed build and are very plastic and HOLD THEIR SHAPE – which is why our surface dwelling worms build it and can live in it.

We decided to build a larger scaled steel framed worm bed with really flimsy sides to see if we could finally prove our point to the engineers. It worked well … very well so we invited the engineer to check it out once nearly full of castings. He came, concurred and then, at extra expense, changed the metal sizes and thicknesses marginally and made very little difference, that we could determine, to the weight and costs.

We harvested over 50 tonnes of castings from those beds, transported them to Redland Bay and commenced another larger experimental bed within old chicken sheds … that worked too.

An important part of these experiments was to establish a bed on all sorts of food types: manures, food wastes, green wastes, sawdust, cardboard, hay, plus foods that should be impossible for worms to handle. Such a bed that would still produce sufficient worm offspring to start another larger bed and then another and so on, for a suitably sized organics recycling project of extra significance.

We now have enough castings and ‘worm-power’ to look at such a project.